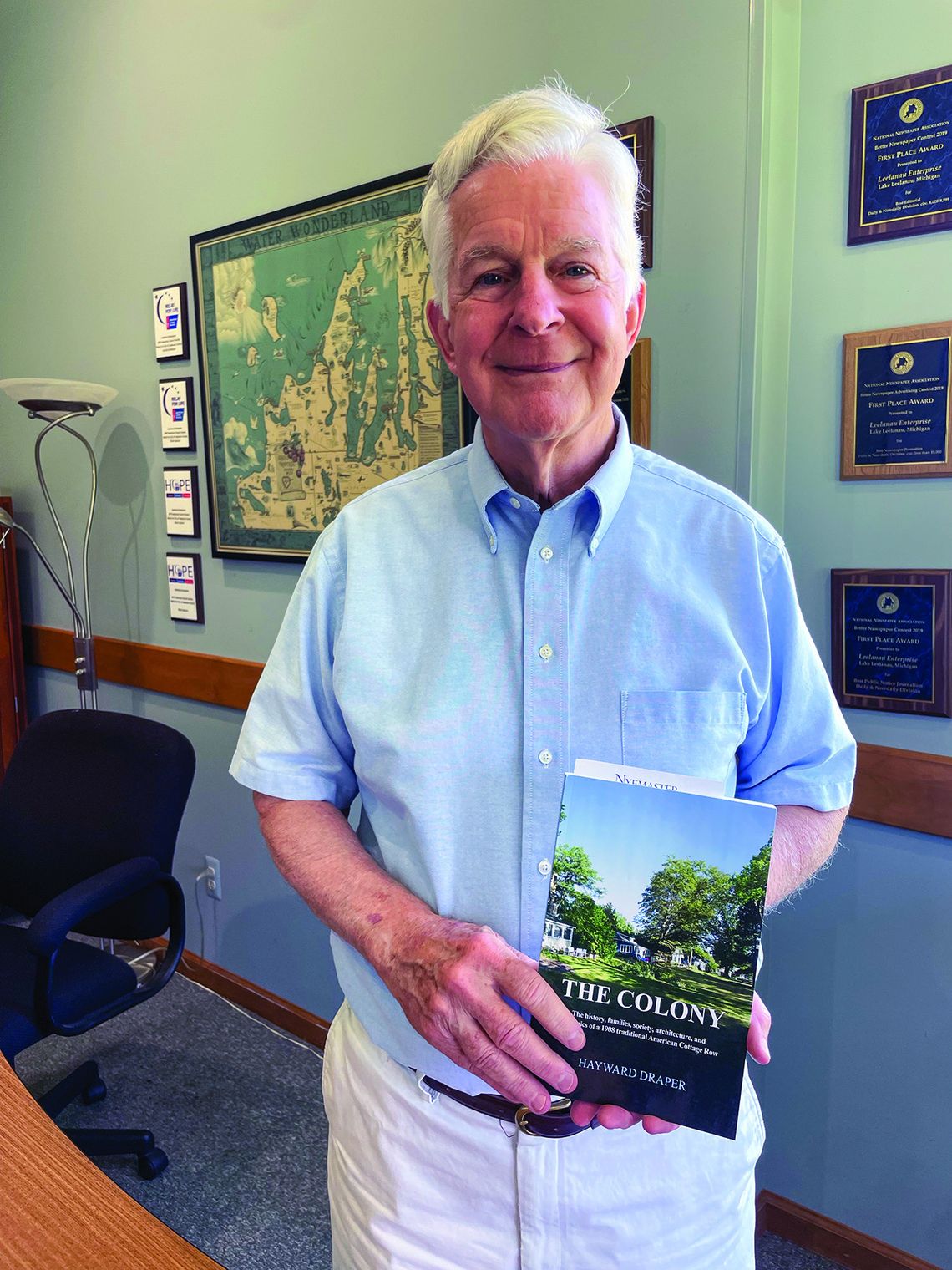

Lake Leelanau resident Hayward Draper released a new book just in time for the Biggest Fourth in the north.

‘The Colony’ by Hayward Draper tells the stories of six families who created one of the few remaining communal cottage rows left in the United States, located just across the lake from the Fountain Point Resort on south Lake Leelanau.

In his 144 page book (including many old photographs), Draper guides you through the early years of white settlement in the area in 1853, and then what led to the founding of Fountain Point Resort in 1889 and The Colony in 1908.

PLEASE LOG IN FOR PREMIUM CONTENT. Our website requires visitors to log in to view the best local news.

Not yet a subscriber? Subscribe today!