Chelsea Tarvainen’s home-based child care business in Petoskey has operated at full capacity since she first became licensed in November 2021.

With no employees, Tarvainen can only have up to seven kids at a time. She gets steady calls from families about her waitlist, which already has more than 20 families on it.

“It is insane,” she said. “There are so many babies being born and people getting on the waitlist as soon as they find out they’re pregnant. There’s no one I can really even recommend for them because all the providers in Petoskey are full.”

Such is the situation across much of Michigan, where 89% of kids live in places with insufficient child care services, according to Michigan State University’s Child Care Mapping Project. The shortages are especially acute in rural areas and throughout northern Michigan.

An MSU study released earlier this month found a lack of access to child care costs the state’s economy $2.9 billion in lost productivity as parents are forced to stay home from work to care for their children.

But a new $400,000 state grant — the only one of its kind this year — aims to alleviate the so-called “child care deserts” in parts of northern Michigan.

Building on a model developed in Leelanau County in 2022, the Leelanau Early Childhood Development Commission will use that state money to establish new and expand existing child care businesses in Grand Traverse and Benzie counties. The new Infant and Child Care Start-Up Expansion program focuses on increasing the availability of child care for children up to age 6 — with an emphasis on kids up to age 3 — by providing both financial and coaching support to child care providers. The money can cover startup or expansion expenses and training in the areas of child care best practices, licensing and business.

“In order to meet the need in child care, we have to be innovative,” said Patricia Soutas-Little, chair of the Leelanau Early Childhood Development Commission. “I’m hopeful that this trend can continue and there are a lot of people throughout the state that want to do this.”

What it might look like

In 2023, the state approved a new pilot program for home-based child care in Leelanau County. Instead of operating out of a private residence, home-based providers could partner with others to offer child care in another facility without having to open their own building.

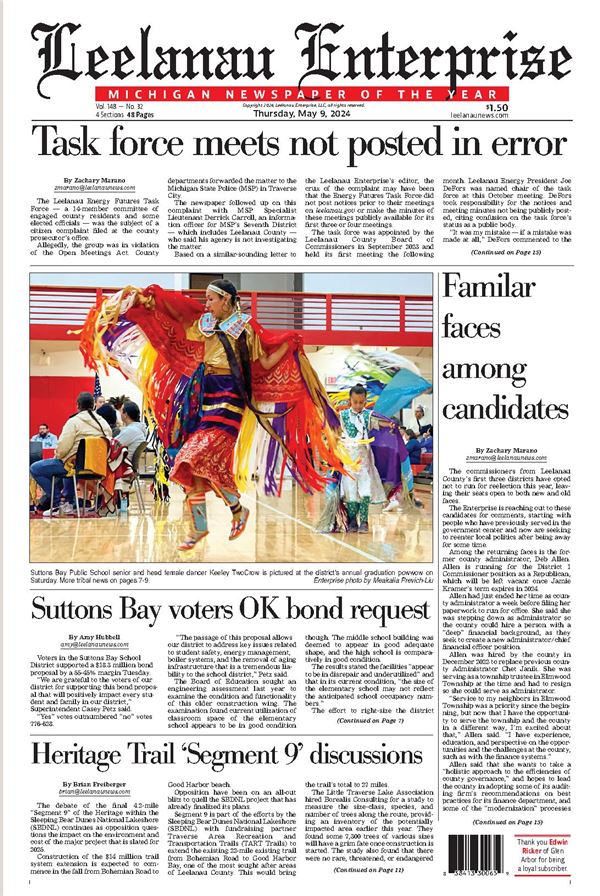

Three of those so-called “micro-centers” have opened in Leelanau County: In December, Sherry Devenport opened Rooted Daycare at Glen Lake Community Reformed Church in Glen Arbor. In January, Betsy Garthe-Shiner’s Dandelion Discovery Center opened in a building owned by the Village of Northport and Renee Suzawith’s Kits and Cubs Childcare opened at Suttons Bay Public School.

Each of the child care operations lease their space for $1 a year, while other partners such as the Leelanau Community Foundation help cover other operational costs.

Cheaper overhead costs have made opening micro-centers in the county easier for providers who said they may not have opened a child care business without that help.

“I actually think micro-centers can be a solution to the daycare dilemma, because, for a lot of people, they wouldn't mind opening a daycare, they just don't want to do it from their home,” said Rooted Daycare’s Davenport. “With this program, it really puts you in a space where you're able to run a business and make money. I wouldn't have done it without them.”

Garthe-Shiner, of Dandelion Discovery Center, said she was at full capacity — 12 kids — this summer. She has a full-time and a part-time employee and hopes to add six more kids to the program in the future.

“There's been such a high need for child care for families in the summertime,” she said. “We’re really proud of what we are building and excited to see where it will go in the next few years and how it will change in response to the needs of our community.”

Soutas-Little said the new state grant might support similar micro-centers in Grand Traverse and Benzie counties.

How it began

In spring 2022, Soutas-Little said, a group of providers and others interested in child care came together to discuss how they could expand options in Leelanau County. A lot of home-based programs had closed, and the group looked at what might have caused that.

The group came to the conclusion providers did not receive business training and families need help paying for tuition costs, Soutas-Little said.

“Subsidies to families is one way to bridge the gap, so to speak,” she said. “It is expensive. Yet, for the childcare provider, they are not making any money. The expense comes from everything they have to do to be in sync with the state code and state rules, and there’s a lot of them. So we were looking at a way to turn it into a win-win situation.”

In 2024, Networks Northwest, which provides workforce, economic development and regional planning services to 10 Up North counties, led a Regional Child Care Planning Coalition that included parents of young children and child care providers along with representatives of schools, intermediate school districts, employers, economic development organizations and local government.

The coalition concluded that the region needs full-time care for roughly 2,600 children up to 4 years old, with the unmet need greatest for infants and toddlers up to 2 years old.

The most widespread barriers reported by parents and other caregivers were availability and cost of care.

Soutas-Little said that, for rural communities, micro-centers and home-based programs are likely the best, most cost-effective options.

“Building a center is expensive and there are a lot of other rules and building codes that come into play that aren't in these other situations,” she said. “They still have to meet statutes for safety and whatnot, but it's far less of a change required, because you already got a facility that meets a certain level of that and they’re already serving families, so it's nice to kind of build on that.”

Although micro-center programs can act as a solution in child care deserts, Soutas-Little said they do not deal with other issues related to an already “broken child care system,” such as the high cost to families and low pay for providers.

“Until we get a handle on universal child care support in some capacity, we’re never going to address all of that,” she said. “We’re going to continue to put Band-Aids on, which is what we’re doing right now, finding ways to supplement the wages for providers, finding ways to help pay down the cost of tuition for families. I think it's going to take a long time, and it has to be a thoughtful approach.”